The Revenge of the Lolloping Snufflebums.

Armando Perigee Festoon

A moral tale about the misuse of eggs

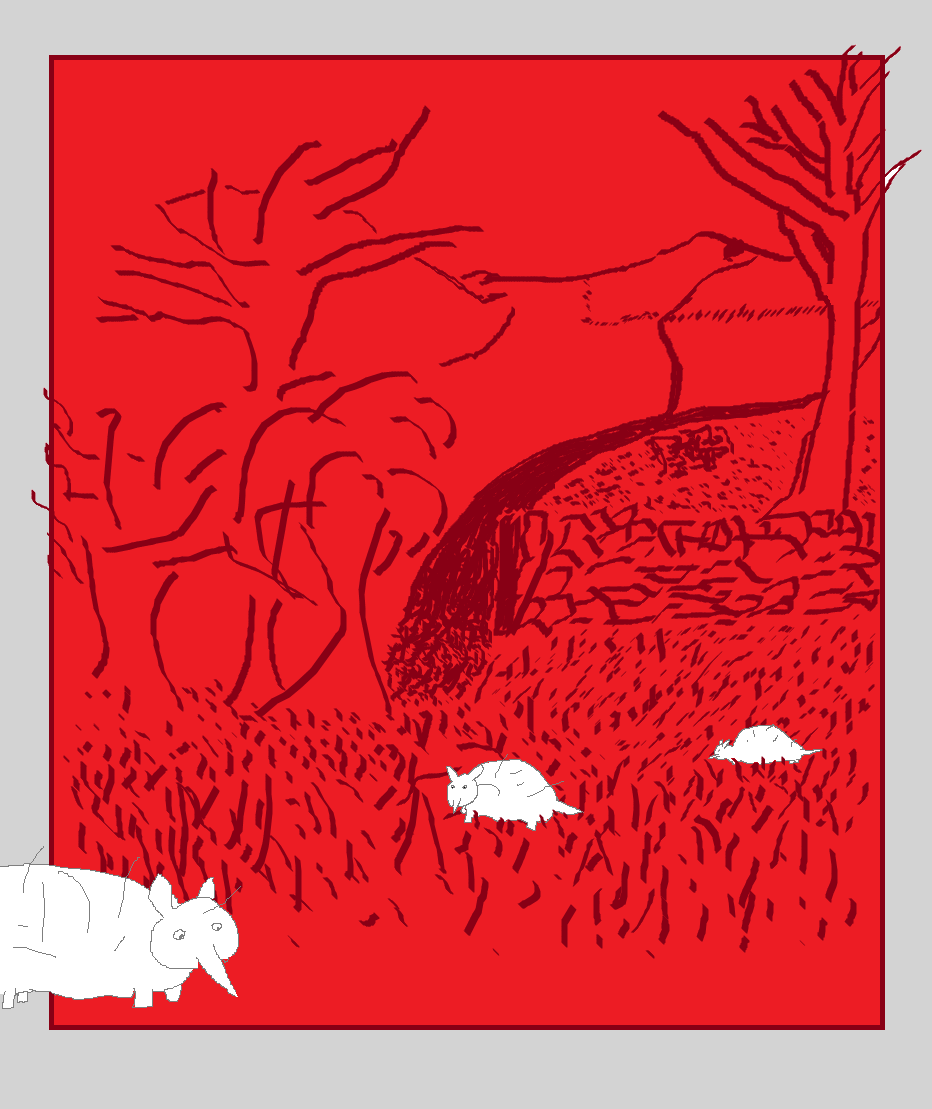

On a high hillside where the grass slants westerly, the frenzy of flolloping Snufflebums lolloped in a flexible pattern of freedom, unconcerned by politics or war and guided largely by the availability of woodlice.

Widely tolerated by the villagers, daily and monthly, the frenzy glid irregularly from common to field and pasture to paddock scratching little holes and investigating damp corners. In its seasonal carousel, as young Snufflebums were born and old Snufflebums snuffled off their mortal coils, the frenzy was ignored by dogs and farmyard beasts and induced only trivial trauma and mild peril in the hearts of those others whose path it traversed.

In all but one, that is. In the heart and the head and eventually the stomach and clenched fists of a single man, the quiet but constant chew-unching of their long jaws, as the hulls of woodlice were shattered to access the tasty flesh within, and the scratch-slipping of the cascade of tiny paws across gravel drives, gave birth to a glowing hatred.

McGregor, for that was his name - appropriate to such a story as this, as bad men are often called McGregor, particularly in England - built up his animosity and his blood pressure with every dark hour he lay awake unable to ignore the quiet snores of the Snufflerams on the lawn outside, and with every sod and clod he ruefully replanted after its impetuous eviction by a Snufflenan whose nostrils were filled with the odour of earwigs.

He was a yeoman by inclination and something in stocks or bonds by background. The stocks, or possibly the bonds, had equipped him over the course of an unmemorable succession of decades with a long number in his bank account, a finely restored, mock tudor, mock Edwardian, mock palace in the environs of Tilebury Chase and a palpable certainty of entitlement to live out his yeomanic fantasies.

In McGregor's view and learning, nothing of the Yeoman's lifestyle had ever involved the need to tolerate Snufflebums. And he was not going to do it.

McGregor had chickens. They were known as 'McGregor's Chickens.' He fed them and read books about cultivating them and paid other men and women to build runs and sheds and laying-trays for their accommodation. He understood, in an academic way, about hen-louse and poultry-bain as well as such agricultural terrors as chicken-foot-rot and premature-moulting. Against these, he guarded with regular inspections and large veterinary bills. Despite all this, his chickens thrived and he was daily wont to collect a goodly five or perhaps four - six on Sundays - fresh laid eggs to satisfy his self-esteem as a smallholder.

One egg a day was all McGregor allowed himself on account of his private surgeon's worries about cholesterol (bad cholesterol that is - not the good stuff which is known as good cholesterol) and an uncertainty about whether eggs counted as 'dairy.' McGregor had heard negative things about ‘dairy' and didn't like to take risks. This left him, every two days, a full egg-box wealthier (except on Sundays when there was a whole box) and able to engage in an honourable way in commerce. Success in commerce is all about contacts, and consequently McGregor did well - supplying his spare eggs at phenomenal mark-up to a friend from his stocking and bonding days who had retired to run a well-regarded organic, free-range, fair-trade, wheat-gluten-soya-peanut-dairy-calorie-and-content-free delicatessen in Knightsbridge (London).

But, strangely, McGregor did not become the bonny and boisterous influence of joy and goodwill which might have been expected from his yeomanly successes. He brooded almost as much as his chickens. And he was not a well-loved conversationalist. In that respect he crowed as much as his cock (who was a noisy feller). He was bothered. He was troubled. And the dream idyll of bucolic bliss, which he was sure his services to bonds and stocks deserved, remained unsatisfying.

As the fault could not lie in him nor could he find real issues of cavil in the well-connected semi-pastoral picture-village of his choice, his chagrin gradually began to focus on a cause which lay outside his image of normal agrarian life. Snufflebums. Snufflebums were not supposed to feature and yet they did. In a large way (for well-fed Snufflebums are individually large and the frenzy had grown to a non-trivial number) Snufflebums were the one thing he had not budgeted for and were the one thing which increasingly marred his existence.

Years of anxious worry about the well-being of his bonds (or possibly his stocks) had made him a fitful sleeper. It was not unknown for him to wake suddenly, all a-sweat, with terrible images of the dangers to which the Hang-seng might be exposing his gilt hedges or the dishonourable intentions of the Nikei towards his long-term swaps. He did not like to think of his future options hanging out on Wall-Street late at night when good Europeans should be abed.

And, sad to relate, the nightmare scenarios of rampaging bull markets and bears unleashed on the borse had been unquelled by his own retirement. The darkest part of his mind (the part which is only accessible in the dark) was still packed with - and clearly overflowing with - the dreads of traders. Many a midnight, did McGregor still find himself staring blankly at a bedroom ceiling in the perfect silence of his creaking house, where the pipes rattled, the owls hooted, the chickens made sleeping-chicken-clucks and, most of all, Snufflebums made noises on his lawn.

One night, a breaking point was reached. A particularly vile dream in which he had failed to make a turn on the dead cat bounce of a capital run on the Dax, had scattered the clouds of Morpheus to such a degree that his hair - or at least the strands that remained to him - had stood on end like fretful porpentines and he had been pumped so full of adrenal energy that he too had been compelled to stand on end like a fretful porpentine and pace about beside his original (reproduction) Elizabethan, double-glazed, 1648 sash picture-window with tilt function.

The view from his bedroom commanded a powerful aspect over the sweeping, Capability-Brown (inspired) lawn with duck-pond of his desirable detached mansion-house where it stood back from the peaceful village road at the heart of the thriving and welcoming community, which was asleep. Also asleep, and rather closer than the aforementioned members of the welcoming community, who were one-and-all located in their own desirable residences (or possibly the desirable residences of their very close friends), was the frenzy of Snufflebums.

The frenzy had elected to sleep, decoratively, around McGregor's duck pond. The ducks did not mind this. Ducks are not scared of Snufflebums. They have no cause to be.

McGregor, however, did mind. It was the third time this week that he had found the frenzy on his doorstep and, as may have been alluded to previously, he was not fond of Snufflebums. He did not like their independence of mind nor their disregard for property rights and the law of trespass. He also did not like the noises they were making. For Snufflebums are not quiet sleepers. Many of them are fat, and fat things tend to snore.

"How can I sleep with those infernal creatures outside my window making those infernal sounds?" McGregor asked himself, rhetorically and silently. Then more forcefully, and aloud, he asked the bedroom.

Subsequently he flung open the sash window on both its hinges and asked fundamentally the same question of the Snufflebums in a voice which was undeniably loud enough to carry to the duckpond. He also added some suggestions.

The Snufflebums ignored him. They were asleep and Snufflebums are deep sleepers who do not like to be disturbed. If Snufflebums came with a door-handle (which they don't) they might well have hung a sign on it every night which read "do not disturb." They would probably not have bothered with the one you sometimes get in hotels which says "maid service required."

The moon glow landed softly on the gently rising and falling white fur of the frenzy and made the Snufflebums look absolutely nothing like ghosts. One of the Snufflenans turned over in her sleep and fell off the duck-pond wall where she had been perched. There was a faint splash.

McGregor increased his volume and his demands. The Snufflebums shut their ears (a useful trick and one which other species, including humans, ought to evolve - put it on the list, after inbuilt rocket-power and fingertips small enough to type on smartphones) and pretended not to understand. Snufflebums generally don't let on that they understand English (particularly when spoken with a London accent).

McGregor decided that compulsion was required to obtain the attention of the frenzy. But there were quite a lot of Snufflebums and there were stories in the village that they could give you a nasty nip if you approached too close. Snufflebums have been known to grab an opponent's finger with their tiny razor teeth and not to let go until they were given an apology and a fully executed deed of retraction, witnessed by three observers including at least one Snufflebum. Also McGregor was in his He-Man pyjamas and he didn't want the villagers - or the Snufflebums - to laugh at him.

But he was also livid, both in temper and complexion. He needed somehow to scare off the frenzy. And it came to his mind that, like embattled nobles of old, he held a strong defensive position and to his hand were numerous missiles which could be used to disperse the angry mob of attackers. Sitting in the pantry, beneath a delivery note for a delicatessen in Knightsbridge (London), was an entire week's worth of eggs - four boxes of perfect cannonballs (three from the weekdays plus one from Sunday). And the Snufflebums were at a range well within his, cricket-ball-honed, abilities as a marksman. Donning his slippers (which were shaped like purple dragons, for some reason) he scampered down the seasoned-oak stairway and past the papier-mache stag's head.

The first egg landed directly in front of a dripping Snufflenan who had just succeeded, with some difficulty, in dragging herself out of the duck pond. She looked at it with scientific enquiry. It was an egg. It was broken and some of the white had splattered her snout. She did not like it.

Snufflebums do not like raw egg. They prefer their eggs poached and ideally sprinkled with toasted ants. As far as they are concerned, raw egg's best use (other than to poach) is to feed to millipedes so that there are more millipedes to eat. Snufflebums are well informed of the subject of millipedes. Particularly the biting kind. The kind which likes raw egg and which lays millions of eggs.

Anyway, the Snufflenan's night had already been interesting enough and she had no desire to investigate this broken egg. Instead she decided to lollop around to the far side of the duckpond where she could make a little space to sleep by uprooting an inconvenient stone gnome which had been unsuccessfully fishing in the duckpond for long enough to know that there was little profit in the venture.

The second egg landed on the hindquarters of a Snufflekid with a lively imagination. That Snufflekid woke the entire frenzy in under ten seconds with her descriptions of alien invasions and bullets being fired from flying saucers. This was not believed and the Snufflebums gathered instead around the egg which was still gently rolling along a flagstone path - unbroken (except for a small crack) due to its soft landing on the Snufflekid's padded bottom.

The appearance of the egg was surprising, but the frenzy showed no signs of undue worry. The general inclination appeared to be to live and let live and to ignore the egg while it rolled to its final resting place. Most of the Snufflebums still had their ears shut so were oblivious to the ranting shrieks coming from McGregor's window.

It was only with the third egg that the Snufflebums' annoyance began. This one bounced off the ear of one of the most influential Snufflenans who happened also to have been suffering from painful teeth after getting some beetle-shell stuck between her fourth and fifth canines and not having any dental floss (or legs long enough to floss effectively). She became irate and the frenzy took the hint.

McGregor made a mistake that night of using up the rest of his ammunition. All twenty four eggs had been lobbed at the circling frenzy and, now that the Snufflebums were awake, no really satisfying hits had been recorded. Nonetheless, the frenzy had not departed and come dawn they were still camped out by the front door, the back door, the side door, the pantry door, the double doors to the cellar which were designed to allow the delivery of beer-kegs, the French-doors which allowed access onto the patio, the car-port door, the chicken-run door and every window from which a moderately fit pensioner might have been able to scurry. They lay patiently on the grass or in hedges or snuffled around in bushes in search of woodlice. Plainly they were going nowhere and neither was McGregor.

A postman came and went. A few villagers responded to McGregor's calls, inspected the scene from the roadside, took one look at the razor-sharp teeth of the Snufflebums and departed with their fingers balled-up tightly and fists thrust deep into pockets. Late in the morning a delivery man from a delicatessen in Knightsbridge (London) appeared and left empty-handed. These the Snufflebums left unmolested, however, any apparent intention from McGregor to leave the house or to accept anything from the visitors caused and immediate ripple through the frenzy which quickly resulted in a slamming door.

Three days passed. The snufflebums remained in place. McGregor's supplies dwindled. Soon he was out of whisky. Then the beer ran out. By the third day he was so desperate he was even eyeing up the advocat. He was obliged to enforce rationing upon himself. Nonetheless, at breakfast on the fourth day, he finally accepted the inevitable and drank the last can of cider.

It was also at this point that he realised that he was almost out of food. No bacon, no humus and the wheat-and-gluten-free paninis were so stale they no longer tasted of cardboard. He would soon starve.

Except of course that he still had access to the chicken-run. He had not been out because it would expose him to the glares and glinting teeth of the Snufflebums. However, there was a sturdy wire fence between them and him and the laying trays would no doubt be awash with eggs. Day two of his incarceration had been a Sunday so there should be over a dozen eggs by now. It was pleasing that, as a self-sufficient yeoman, he was able to produce his own food without the need for Waitrose.

It was a brave thing for McGregor to access the chicken-run. As he entered it, dressed in clothes he had bought from the Army-surplus store and walking boots which had been advertised in Selfridges as the most waterproof footwear ever designed (excluding wellington boots, waders and the boots attached to diving suits), the entire frenzy gathered outside the fence of the chicken run. They stared at him and bared their tiny, pointy teeth and snuffled and lolloped and crunched their way through piles of woodlice in a meaningful way. It would be lying to suggest that McGregor was not scared.

However, he was also hungry and almost entirely sober. And he was given confidence by the fact that the Snufflebums had clearly tried to breach the chicken-run fence and had only been able to make a hole slightly larger than an egg. As has been mentioned, even Snufflekids are large (and probably full of cholesterol - good or bad) and there was no hope of them reaching him through a hole that size. McGregor smiled at the impotence of the frenzy and resolved to outlast them even if it involved drinking water from the tap.

He was in luck. In the four days since he had last collected the flock's bounty (one of which was a Sunday), no fewer than nineteen eggs had appeared. Arms full and ignoring the fluttering of the hens and the chomping of the watching Snufflebums, McGregor fled back into his house provisioned for an extended siege.

McGregor was not going to make the mistake of throwing away his supplies this time. No more missiles from the picture window. All nineteen eggs were neatly lined up in the fridge and labelled with a marker-pen for consumption. Two eggs, three times a day and he should live. He would exhaust his stocks in three days' time at which point he would have to make another visit to the chicken-run to get him through to Sunday where there would be another big harvest.

It was only after dinner that night (two eggs, fried and sprinkled with a little black pepper) that McGregor noticed one of the eggs had a tiny crack on it and resolved to eat that in the morning before it went off.

The Snufflebums were particularly active that night. McGregor could hear them from his bed pacing up and down the lawn, pushing the gnomes over, snapping thorns from the roses so the black-fly and aphids were easier to reach. But this time he was pleased. He smiled to himself and laughed at them. He was secure for ever with his egg-harvest and his walls were thick and impregnable.

Also that day he had taken a call from his friend in Knightsbridge (London) who had promised to come down in his Range Rover. And they had arranged a surprise for the frenzy. The friend had taken delivery of two modern air-rifles and a really unnecessarily large number of pellets. He had also obtained licences at the post-office for the right to shoot vermin. There had been no box on the form for Snufflebums but the post-office lady had allowed him just to tick "other". He had also ticked "pigeon" for old times' sake.

"Now let's see you lollop!" thought McGregor, who wasn't a very nice man. Dawn dawned as dawns do. The frenzy was very active. McGregor could see that they had begun to assemble something on the lawn from pieces of broken fence-panel, uprooted gnomes and dismembered garden furniture. It was hard to say what it was, but it looked like a platform, maybe six inches from the ground, whose legs were made of steel and were sunk into little puddles which had been created by diverting the stream from the duckpond. It occurred to McGregor that he had not known Snufflebums were capable of such co-ordinated feats of engineering and it was surprising that, as they were, they had not previously designed some siege engine or device to access the house, or perhaps the chicken-run.

Nonetheless, time now was on his side. The air-rifles and his sturdy companion would be with him by noon and Snufflebums would be lolloping for the hills five minutes later with pellets whizzing about their ears and bruises on their capacious bottoms. Perhaps he would stand on their platform and give a small victory speech while sipping the champagne which he had thoughtfully asked his friend to bring. He listened to the snuffling of the Snufflebums and the singing of the birds and the distant wheeze of the village bus and something else, a countryside sound much like the rasping of cicadas which he had never heard before. He smiled. Today he was going to win.

But first - breakfast. As victory was so near his rationing was no longer necessary. He would have four eggs. One poached, one fried, one scrambled and one grilled. He slipped on his dragon-slippers and skipped happily down the seasoned-oak stairs and past the papier-mache stag's head into the kitchen. Passing a ground floor window he noticed that the frenzy had formed up on the lawn around their platform, almost as if they were defending it. Well, they could have their rituals if they liked, it would soon be no more than academic.

The noise of cicadas (or whatever) was louder downstairs and particularly loud in the kitchen. It was actually more a scrapping scrabbling sort of noise as if billions of tiny feet were scratching over hard surfaces. Very odd, he'd never heard anything like it before.

He took the frying pan, poaching pan, mixing bowl and grill pan from their respective hooks and flung open the fridge to retrieve his eggs. The scratching cicada noise boomed out of the fridge the moment the door was open.

McGregor scrambled backwards and tripped over a kitchen chair landing heavily on his bottom. The world had turned red and slithery and loud and a liquid flow of maroon was pouring from the fridge. He turned and fled waving the frying pan around in a hopeless attempt to bat away tiny little red wires which seemed alive and seemed everywhere, before finding himself in the hall, beneath the papier-mache stag's head stumbling and terrified and panicking from fear.

It was only then that he realised that the red tide which now was following him from the kitchen and small parts of which were clinging to his He-Man pyjamas and crawling into his dragon slippers and biting and stinging his pasty skin, was made up of millipedes. The biting kind. The kind which likes raw egg and which lays millions of eggs.

The kind which, if introduced into a raw egg (which might perhaps have been unbroken except for a small crack after being thrown through the air and landing on the padded behind of a Snufflekid, and might have been pushed back into a chicken-run through a hole in the fence) might lay lots of eggs, eat merrily and then, with its family, break out inside a fridge where there were other eggs to eat. The kind which liked biting people.

And the millipedes were following McGregor. They had eaten all the eggs in the fridge and were hungry. McGregor was tasty. He turned and ran. He flung open the front door and dashed out onto the lawn. There were Snufflebums there and Snufflebums eat millipedes - perhaps they could save him. He charged towards the Snufflebums and their platform, the soles of his dragon slippers striking sparks from the gravel.

The platform was raised above ground with legs buried in puddles so millipedes could not climb them. He would be safe on the platform - if the Snufflebums would let him reach it.

But the Snufflebums looked immobile. They saw the millipedes but none moved to eat them. McGregor had only a small lead before the Trillipede overwhelmed him and he was bitten and stung until he looked as red as a Scot on holiday in Crete. What could he do to win over the Snufflebum frenzy and reach safety on their platform?

An apology, of course, was all it took. McGregor found the scrap of paper on which the apology was written and the pen which the frenzy had left out for him on the flagstone where the egg had rolled. He signed his name quickly and recited the apologetic words which were set out on the paper. Then with seconds to spare he sprang onto the Snufflebums' platform and stood surrounded by a biting sea of red which could not reach him.

The frenzy took the paper and hung it on the gate of McGregor's desirable country mansion and Yeomanry. They lolloped in the direction of Bishops paddock where there had been a glut of woodlice the previous week.

McGregor was finally rescued by his friend who backed the Range Rover up to the platform so he could climb in through the boot. They didn't drink the champagne.

McGregor moved back to Knightsbridge (London) shortly after.