At a loose end at the end of her university term, Maria Jennings finds herself taking a trip to Tilebury to see the house in which Sophia Morton, daughter of the Eighth Earl of Chennan lived out her life in the first part of the nineteenth century.

A children's rhyme from her youth and the coincidence of reading about Sophia's violent death are enough for Maria to want to know more about her.

The more she enquires the more she discovers the strange life Sophia lived, including incarceration in a tower, investigation by an early psychoanalyst and an apparent affinity with wild beasts.

Her enquiries bring her into contact with a number of Tilebury's current inhabitants and she observes an increasing number of inexplicable events.

Extract - first section. Please contact Tilebury for full novel

Sophia Morton

Edward Morton, Eighth Earl of Chennan's third child was his only daughter. She was born in 1801 while her father was away inspecting a village he had purchased in Wessex. He named her Sophia because he hoped she would be wise.

She grew up clever rather than wise and troubled her tutors and nannies with an unwillingness to concentrate on foreign languages, genealogies or art. Instead, she insisted on reading romantic books and appreciating humour and theories and dogs.

In 1832, they buried her in the family's Lincolnshire estate where she had lived a whole year as a baby. Still in a basket, she was carried directly from her mother's funeral to her father's new house in Tilebury. There she spent the rest of her life.

The tombstone carries her maiden name because she never married. It does not record that she spent the preceding ten years behind a locked door in a well furnished tower suite. Nor does it mention that her body was found at the bottom of that tower, broken and bloody and bitten by dogs on the earliest dawn of that year.

She was not a suicide but the victim of a weakened mind. She had slipped when sleepwalking along the fashionable castellations of her turret room. Suicides were inconvenient in 1832 and the Earl had no more intention of the church mistaking her death for such than he had of formalising her madness by enrolling her in a clinic.

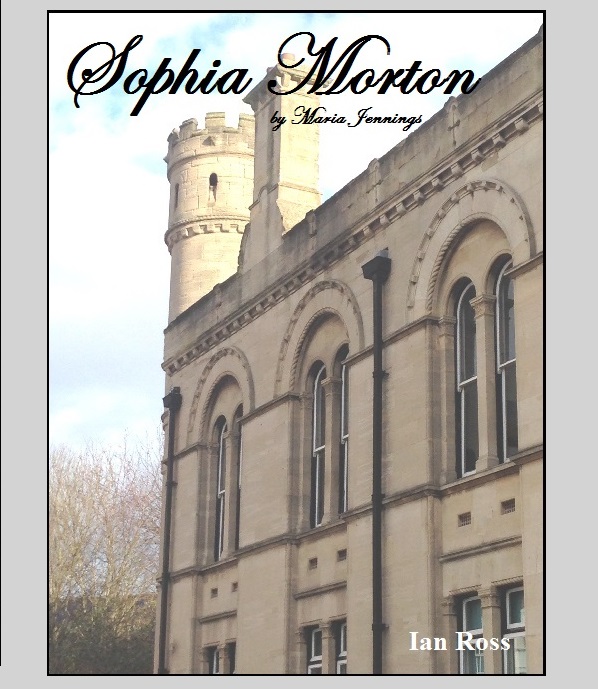

Her prison was not austere. She had rooms on three floors to herself connected by her own spiralling stairs. The lowest floor, still some thirty feet from the ground, contained a bedroom, closet and breakfast room. Above were parlour and sewing room and at the top, within an open circular walkway on which she took exercise, a turret room.

The five, evenly spaced, high windows of her turret room command extraordinary views over everything which happened in the village. In its centre was a desk with a good lamp and pens and a high pile of fine blank paper. Around the walls between the windows were hardwood bookshelves stuffed with romances and biographies and horrors. The most worn were the three volumes of the author-less first edition of Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus published in London in 1818, four years after the scandal of the Bethlem Royal Hospital and four years before Sophia could no longer be allowed free run of the house. Upon her death, a family retainer, perhaps a footman, collected all the written pages strewn and stored around the desk and placed them into a trunk. The trunk was made of teak and had originally carried spices from Arabia to the second Earl of Chennan. The footman placed a few of Sophie's personal objects on top of the papers and sealed the whole with bands of iron.

The following year the Earl completed the sale of his remaining property in Tilebury. Tilebury House and Tilebury village held nothing for the Earl following the Reform Act and he was beginning to suffer from the gout and aching hips which would reduce his final years to inactivity. He was drawing in his horns and rationalising his property before spending a relaxing retirement, first in a bath chair in Royal Lemmington Spa and later in the clear air of Salzburg.

The trunk accompanied him back to Lincolnshire where it, and its contents, were forgotten in a garret, like many literary greats.

During his daughter's decade of confinement, the Earl of Chennan was a busy public figure. As a peer and a magistrate and a landlord in three counties, his circuit of duties was constant. His reputation as a philanthropist and a modern thinker required constant sustenance and his reconstruction of community buildings was a drain both on his fortune and his concentration. The schools he founded for the sons of disadvantaged tradesmen expected some of his energies in exchange for their existence and although the post he held in his majesty's Board of Admiralty was mostly honorific, it nonetheless required his regular attendance in London ballrooms and theatres. Without a wife or a daughter to manage his household and with one son who was fond of sherry and another who had learnt nothing from his captain's commission beyond the rules of piquet, his family were not well placed to reduce his burdens.

For this reason, the Earl was unable to give his daughter the personal care and attention he would have liked. That fact weighed upon his conscience and led him to engage the best available doctor and nurses to attend upon her in his place. During a period of some years he also purchased the affections of an educated and charming companion to sit with her and engage her in conversation.

From each of these angles he requested regular written updates to ensure that he was fully informed both of his daughter's situation and the quality of the care which he was providing. On most occasions he read their letters within, at most, a few days of receipt. On all occasions he handed them immediately to his steward to file in chronological order.

Following Sophia's interment, the steward, who at that time was Richard Grey, the fourth son of Sir Dornauld Grey, Bishop of Harrogate, bundled all the now redundant reports in green ribbon and ordered that they be placed in the little library of Chennan House, Holborn where all the family records resided. They remained there until Chennan House was sold between the twentieth century wars to meet death duties for Lady Alixandra Morton, last countess Chennan.

One of the Earl's many enlightened acts of generosity in Tilebury was to renovate the Tudor church. He did it, not to be praised, but to discharge the trust which, as landowner and nobleman, was placed in him. As a respectable man and a member of the church, he recognised his obligation to give the community a centrepoint which it must sorely have missed. A church without a vicar is of no value, so the Earl also retained, at the personal cost of a large part of the church's tithes, a young man from Oxford to minister to the congregation.

The vicar was a man with a social conscience proper to his time, estate and the good opinion of his employer. He was also respectful of history and the use to which men of the future might put the learning of the past, meaning in that case, his own time. He was well steeped in the glories of classical times and naturally concerned by their subsequent loss during the dark ages from which his own empire had only now substantially emerged. Fearing that something similar might again occur, and wishing to preserve what he could of the enlightenment of his own age, including its concern for the conditions of all men, whatever their class and station, he had taken upon himself the task of noting the events of his town and explaining them in terms of the gradual triumph of moral truth over barbarism, paganism and superstition. In pursuing this purpose, and with a decent respect for the importance of displaying kindness and sympathy to both rich and poor, he took steps to comfort the most troubled member of the family of his immediate patron and employer, the Earl. Unfortunately, the illness which gripped the Earl's daughter was too great for the vicar to handle and she declined to receive his visit.

The vicar, not insulted, as that would have been incompatible with his calling, but perhaps a little piqued by the rude terms in which Miss Morton had shouted her apologies from the castellations of her tower, had written a few observations on her state and upon village gossip as a purely historical parish record.

These notes remained with the church until it was deconsecrated in the late twentieth century when, by an oversight of the local diocesan lawyer, they passed into the possession of an educated and well meaning lady who had founded a small museum of local artefacts.

Through most of the ten years the honourable Sophia Morton spent in her tower suite, she was not permitted visitors. The vicar would have been permitted, of course, had he been wanted. When it was clear that he was not, the Earl had even offered to arrange for a Catholic priest to attend. He was an open minded man and his family had never fully committed to its convenient sixteenth century apostasy. However, this option seemed no more welcome, so he ordered that her circle should remain limited to her professional carers, the family itself and certain carefully chosen servants.

However, one exception was permitted. The Earl was a modern man and open to promising developments in all fields of science including the study and treatment of failings of the mind. Hearing of the work of an eminent man in Weimar he made it known that if this gentleman could converse in English and found himself in the Kingdom, he would be welcome to conduct an examination of the Earl's daughter. After some years, the scientist accepted and, making use of the Earl's patronage to maximise the benefit of his visit, processed through England's wealthy families in the summer of 1829 conducting research and prescribing treatments to a number of unfortunate individuals who spent little time in Society.

Due to the Earl's particular welcome, however, Herr Doktor Harold Von Snedorf spent more time with Sophia than with any of his other patients. Finding her case of particular interest and feeling bound to be worthy of the generous contribution the Earl had made to the running of his investigative clinic, the Herr Doktor prepared a very detailed analysis of her symptoms and his recommendations.

The Herr Doktor took such time and care over this document that he was sadly unable to complete it before boarding his return ship at Plymouth. It consequently reached the Earl some time after the Herr Doktor had left the country. Some of the suggestions made by the Herr Doktor troubled the Earl and he never took the steps recommended. Instead, he kept the report in a drawer of his own desk in the House of Lords until after she died when he was pleased to acquiesce to a request to loan it to the hospital of St Peter's in Bristol. It was never returned and was eventually catalogued into the library of Bristol University when St Peter's outlived the funds with which its founder had endowed it and was dissolved. Herr Doktor Harold von Snedorf never returned to England.

But it was none of those sources which introduced me to Sophia Morton. It was a children's rhyme floating unnoticed in my head which reappeared one morning after a party at a friend's house.

As a teetotal insomniac I was awake too early, waiting for everyone else to rise. I slid off the converted sofa-futon I had shared with my cousin and tiptoed about the house trying not to stand on the limbs and fingers of those who had chosen to sleep on the carpet. Winding up in the devastated living room I squatted on an unclaimed beanbag and noticed a gaudy book lying on the coffee table.

I remembered the book from the night before. It had been pulled from the shelf in the early hours of the morning by a lively boy with green eyes and big teeth who was making a limbo bar from two stacks of books and a golf club. Sorting the books for thickness so both piles would be the same height, he had discarded this one and dropped it, surprisingly respectfully, on the table. No-one, myself included, had taken any notice at the time as the sight of my cousin's awkward shuffling and bending had been too distracting. However, something about it now, in the growing morning light, caught my eye and I picked it up mostly to defray my boredom.

The book was called Tilebury, a History and was written by a Dr Ange Harding. Although Dr Harding had clearly researched her subject thoroughly, she was not a natural writer and I found her descriptions un-gripping. I flicked through black and white photographs and illustrations without interest and decided to return the book to its shelf. However, just before I closed it, I thudded into the rhyme. The force of recollections flooding my mind made me feel as if I'd crashed into a wall.

Here is what Dr Harding had to say:

'Many children's rhymes and poems are said to come from oral traditions and recollections of real historical events. Most commonly "Ring, a ring of Roses" and "humpty dumpty" are said to reflect, respectively, the coming of the Black Death and the destruction of one of the siege cannons at Gloucester in the civil war.

However, it is my belief that only one such ditty owes its birth to Tilebury. Although little known, it has survived down the years - indeed I have spoken to many villagers who remember the hopscotch steps which accompany it - and has been immortalised by local artist Heather Reedman in her beautiful carving in the memorial garden on Brick Street beside the William Jenns Primary School. It is of course:

Out she ran, and in she ran and so they locked the gate,

So out she flew and in she flew and danced among the fete,

And there she flapped and then she snapped,

And ignored the warning call,

Oh, Sophie, Sophie lying at the bottom of the wall.

The story certainly records the death in 1832 of the honourable Sophia Morton, daughter of the Earl of Chennan, found beside the wall at the bottom of Tilebury House tower the morning after the midsummer fayre held, in those days, on the village green. She is said to have slipped and fallen from her bedroom in the tower in the early hours of the morning after being seen dancing around the bonfire with other villagers some hours before. A modern and unromantic interpretation might suggest that she also partook of some of the local cider commonly brewed for the event and suffered her accident accordingly.'

I had never heard of Sophia Morton. It was the rhyme which struck me. I had a clear image of staring up at an old lady who had taught it to us at my infant school in Broadway. She was fat and pale with straggling hair and dark patches below her eyes and she was gone almost as soon as she arrived. But the thing I most clearly remembered about her was the strong country accent which I struggled to understand and the rhyme which I had asked her to repeat a dozen times until I puzzled it out. Even now I found that my version differed subtly from the words in Dr Harding's book. The last line in particular, I distinctly remembered was different and repeated. The words I knew were:

'Oh Sophie, flying Sophie at the bottom of the wall,

Poor Sophie, dying Sophie at the bottom of the wall.'

I don't know why I was quite so floored by this recollection. Perhaps it was the images of childhood it brought back and the sudden clarity of people and events I had not thought of since. Perhaps it was something to do with a realisation that dying Sophie had been a real person. Whatever the cause, I put the book aside and forgot about it entirely when the boy with the green eyes stumbled into the room.

Continued...