I Found a Book.

Ian Ross

I found a book in the street in the morning. It was a children's work book of the type they used to call a ‘cahier' in French classes. The name has stuck with me. Perhaps it had fallen from a bag or a satchel, or whatever else school children now carry.

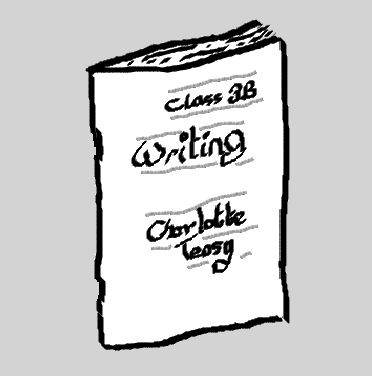

On the front, between pencil ruled lines, it said in loopy handwriting, "Class 3B. Writing. Charlotte Teasy." I took it with me because I had decided to read it. Unless, of course, fate intervened to stop me.

I held it openly in my hand and looked around for an owner. Perhaps Miss Teasy would run back to claim it. Perhaps her harassed mother would appear, feverish to find it and get on with the day's itinerary. If fate presented such a claimant I would do my social duty and hand it over unhesitatingly. Restitutio in Integrum the lawyers might say. I am a professional middle aged salaried man. Just the sort of person who can be relied upon to take care of someone else's property. I am as trustworthy as any lawyer and possibly more trusted than most.

On another day I might even have tried to trace Miss Teasy. Or her school, or her teacher. At least I would have left the cahier in full view. I would have put it carefully away from the puddles and the careless splashes of passing boots. On a wall perhaps. Or maybe one of the flat tops of the bridge struts.

But not today. Today I was practising being a different sort of man. Already I felt myself metamorphosing. The nature within my chrysalis had dissolved and was now reforming, silently and, as yet, unseen. When the moment came for me to break through the pupa walls I would emerge fully formed, different in essence.

Not a butterfly. Something much more parasitical.

The transformation had been some time coming. Some time even after I had decided I could not stop it. That was after my father died. Each day I had suppressed it and had succeeded in retarding its growth for years. Patience was my watchword. The best stew is matured slowly. I have learnt never to act until all the pieces are to hand and in place.

There was little chance Charlotte would appear before I reached the office. It was only a hundred yards. The last hundred yards of the two miles I walked every day. The last hundred yards of a marathon I had been running for years. Nonetheless I gave her the chance. I held the cahier out in the hand as if offering it to anyone who might pass. I walked slowly. I even paused at the office door. I scanned the passers-by and the passers-distant. There was no sign of a careless or clumsy Charlotte.

If fate is not interested in me, it must hold its peace. It has not helped me and I ask nothing of it. I went in, broaching the tape at the finishing line. My supporters, friends, admirers and family all gathered to applaud and congratulate me on my achievement and the lonely silence was humiliating.

I had booked three weeks' holiday. I had to request it especially as two weeks is the normal maximum. I had gone to the boss nine months ago and told him I wanted to visit Australia. It is hardly worth taking the flight if you only stay a fortnight, I said, and referred to it as the holiday of a lifetime. I reminded him that I'd never taken more than two weeks holiday since I'd been there. In fourteen years. He couldn't refuse when I put it like that, although he would have loved to. I was squandering all my Brownie points and cashing in all my goodwill. No point in preserving that any more.

With care I had wound down my current jobs. Some I had transferred to colleagues to manage during my absence. I took great care to explain the background in detail so no client would suffer a diminished service. In most cases I tried to pass jobs to the best of my colleagues. Mostly the younger ones - those not yet jaded by a career of slogging in someone else's interest. In most cases my darling clients would get an improved service which was better than I could motivate myself to deliver. My conscience was salved, as least as far as the innocent were concerned.

I was well organised. Being a professional is all about being ahead of the game and I have learnt to be very professional. Far better at my job than those I work for. Better than those who cream off the profits of my labour. But that's not the point. They got there first and, in a capitalist system, latecomers are slaves.

My desk was arranged with neat piles of the papers relating to the remaining loose ends and sparks I had to extinguish before leaving. These were well within my capacity which I anticipated would leave me plenty of time to read the cahier. I put it to one side of my desk beside the loose end spark papers. It was a quiet morning. I had an office to myself as befitted my senior status and long service. That senior status and long service also meant that few visited me for any social reason. I made a few calls to clients and lawyers. Only work or advice brought me my daily human contact.

I checked a client's passport I had received by courier. I had called him earlier in the week and demanded he send it to me. He was my age, similarly bald with similar drooping bags under his eyes. He was, however, far more wealthy. The man I could have been if I had taken a different path. I need it for money laundering checks, I said, which I told him, correctly, is a legal requirement.

He asked me what would happen if he needed to go to the States at short notice and wanted to know why I needed it now, when I'd already accepted a power of attorney from him.

I still need to see it, I said and told him, incorrectly, that the rules had changed. I adopted a warning tone and told him I needed it immediately, or nothing would happen until I returned. I also promised I'd have it back to him by the time he needed it and that if necessary I would book any flights for him in the meantime. I had already done so.

He was angry and unimpressed. He was another client who would never help my chances of promotion. He made me promise to return the passport today, although, I had, nonetheless, decided not to. The lie was exhilarating.

I dropped the passport into the banking papers in my briefcase.

I confirmed arrangements for my absence with a broker who might have made a note or might not have. I assumed this matter was uninteresting to him. Or perhaps he disliked the client who was a Sudanese whose fortune had arisen suddenly from oil contracts. Perhaps he had not invited the broker to the right restaurant.

I looked in Charlotte's cahier. It contained a few short descriptions with ruled titles and dates carefully noted in the top corner. Teacher had handed down titles about the personal aspects of her life and ordered her to talk all about herself. Start as you mean to go on, I guess. Inside the book Charlotte's loopy writing was tidy with large spaces between the words.

A lawyer called me and confirmed receipt of Trust funds. Then I explained an inheritance tax calculation to a disappointed heir. The bulk of the estate was waiting for him in the electronic vaults of a bank where they needed to sweep the warm Caribbean sand from the foyer. It awaited its fate unviolated by, and unknown to, any taxman. Restitutio in Integrum as the lawyers might say. The heir was nonetheless disappointed by the fraction which had to be paid on the fraction known to Her Majesty. No doubt he would complain about how Her Majesty used it.

I had decided to award myself a coffee break - a civilised trimming to life which, most days, was lost to the urgent demands on my time. The activity and efficiency required to save millions for my clients and make thousands for my bosses. Today, however, I would make a special point to take the break. I would earn it with one more task.

I checked the balance on an account for which I was trustee. All the assets of its ludicrously loaded and irretrievably insane beneficiary had dissolved into one pure liquidated number. The chain of digits so long that it was hard to establish the magnitude of the funds without counting up the commas. The details were as I expected.

My one remaining task for the day was to transfer the balance to its beneficiary. There was, however, no hurry - he could wait while I read more about Charlotte.

The first three pages of the cahier contained a composition entitled "Me and My Family." I fetched the coffee wondering whether it should read "My Family and Me." Perhaps: "My Family and I." I deferred this grammatical conundrum to teacher, whose syntax ought to be superior to mine, although vanity and experience suggested this was unlikely.

I learnt that Charlotte lived in a semi detached house in a respectable suburb with her mother and stepfather. I presumed that this was the same mother who had failed to come rushing back to recover her lost schoolbook. I pictured Mum as short and heavy about the bottom.

Stepdad was a purchaser for a department store. Mum was a translator of Spanish and Italian business texts. I warmed to her and her image in my mind lost a stone and a half. Spanish is my language. I have recently been studying the South American Castilian dialects. Despite the reputation of evening classes for dating, none of my fellow students could even remotely have constituted a love interest. I remained without anyone to hen-peck me and give my working hours a purpose. Fate had again failed to divert me from my scheme.

Charlotte's favourite person is a dog named, "Petsy." She does not like the kitchen because of the damp smell in the walls. Her room is above the garage. There was no mention of her father. What if I had been her father? Would I too rank lower than her pets and my successor as her mother's husband? Would I have been a good father? Even if I was, would she have thought so?

Before lunchtime I spoke to the department head. I had to leave at five to catch my plane, I said. I had put all my work in order, I said. I waited for him to grudgingly accept. A decade of exemplary billing stood behind me to support my request. The ceiling which had killed all remaining hopes of promotion smiled encouragingly over my shoulder in hope of sympathy. He could not refuse me to my face. He would have done if he could. He had accrued millions from paying his employees less then he charged clients for their services. His fortune had, however, not softened him. Unlike him I would be different if I could afford to be. I will be kinder, more tolerant, more understanding. I will be generous.

After lunch I discovered that Charlotte liked to spend her spare time dancing using a computer game. She took care to describe how she and her friends stepped on coloured circles and imitated the movements on the screen. She was almost as good as Jennifer and much better than the hapless Kyrie. Even Kyrie was, of course, better than any boy.

Before four pm I instructed the bank to transfer the balance in the trust account. A simple stroke with my antique fountain pen set off a cascade of events which had taken six months to set up. Once initiated it was unstoppable. It was like tipping the first domino in a rally. Did children still do that? Charlotte didn't mention it. I was forced by lack of competition to regard her as my ultimate arbiter of modern juvenile tastes. Perhaps once the music started you could not stop dancing until the song was over.

The system of transfers would take place over the following week. The dominoes would divide into different streams. Some would pass through companies basking in post office boxes in the Caymans or snoozing in Guernsey. Others, like a green backed chameleons, would change colour through the currency exchanges. Certain debentures would be repaid to Frankfurt and guarantees with London banks would be released. Equity would be freed to be traded by bored brokers in New York and Hong Kong. Some time in ten days or so the steams would trickle into an account in some suitably discreet and tax efficient jurisdiction. From there I anticipated that it would be removed in an untraceable form of cash. Peso perhaps, or Dollars or Real.

Such complexity inevitably accompanies large fortunes. While the dominoes fell and the work was done I would be happily on the beach sipping Caipirinha cocktails. I wondered whether I had packed my shades. I had so little time to reach the airport that I had sent all my luggage on ahead. I could not check now. If not I would buy the most expensive ones I could find. Gucci perhaps. Or Police. Are they still fashionable? Were they good? I am out of touch with current designers.

In my last hour I learnt that Charlotte planned to become a judge in order to help people who had been hurt by criminals. She would have four daughters who would help her investigate the crimes and make sure that stolen diamonds and mobile phones were returned the victims. If she had any difficult cases she would draft in Jennifer to help her. Jennifer was very clever - Mycroft to Charlotte's Sherlock. I left Charlotte on my desk next to the files of the rich clients and their taxes. I feared that Charlotte would find real life disappointing. I hoped she would not buy each day's survival with a little piece of her life like I had done.

I put the fountain pen in my pocket. It was a gift from my mother on graduation and the only thing I still had of her before Dr Alzheimer had taken her. She had already been in a home when my father died. The catalyst for my metamorphosis. She had died nine months ago, signalling that the chrysalis was ready to break.

I left everything else I owned. It was the like the dried out skin left hanging on the branch. My taxi was pre-ordered. The traffic was only just building up to evening rush hour. I arrived as the flight desk was closing. Just in time to board with my briefcase as hand luggage. The clerk barely looked at the ticket and passport. He was eager to rush me on board where my first class seat awaited. It is ten hours to fly to Sao Paulo. I had arranged for a man to meet me there who would drive me over the border to Argentina. There would be no need for the tedious formalities. Perhaps I would move on to Chile. I had about ten days to decide before the money arrived to buy back my life. I wouldn't want to pick it up until it was all ready. Restitutio in Integrum as the lawyers might say.